Vacuum and blower systems are commonplace in food manufacturing facilities. Bakeries, flour mills, breweries, and dairy plants are just a few of the many sites where vacuum pumps and blowers are used. While these facilities may leverage both types of systems, vacuum pumps are more commonly used when processing meats, fish and poultry. Other common vacuum applications include maple sap extraction, confection, vacuum coating, and juice distillation. Blowers are frequently found in pneumatic conveying systems for moving dry bulk materials along a conveying line. In these systems, blowers pressurize the material, helping to move it from one location to another.

“When you talk about the food industry, there is such a wide variety of applications using blower and vacuum systems,” explained Russ Ristow, Regional Sales Manager, MD-Kinney. “All you have to do is look in your freezer, refrigerator or your pantry to see all the different products that could relate directly to a vacuum or blower—anything from cheese and dairy, to pickle and meat packaging.”

Several experts from MD-Kinney recently spoke with Blower & Vacuum Best Practices Magazine to discuss opportunities for improvement regarding vacuum and blower systems at food manufacturing facilities. During the talks, Adam Crampton, Russ Ristow, and Tim Wilson of MD-Kinney covered a variety of topics—from the design basics of pneumatic conveying systems, to advanced vacuum optimization opportunities within packaging machines. While general considerations are discussed in this article, MD-Kinney emphasized the importance of evaluating applications from a systems perspective to develop unique solutions for each customer.

Blowers for Pneumatic Conveying

Before delving into design considerations for pneumatic conveying systems, it is important to understand some of the fundamentals. Pneumatic conveying systems move dry bulk materials through a conveying line. Blowers are commonly used to pressurize the conveying line, which moves the product from one location to another, at a given flow rate or within a certain period of time. There are two distinct types of pneumatic conveying systems—dilute phase, and dense phase—and each is used to transport dry bulk materials of varying size, shape and density.

“Dilute phase pneumatic conveying involves conveying a product, usually some type of a dry bulk material, at a low pressure (less than 15 psig) and high velocity. In doing so, the product is suspended in the conveying line. This is the most common means of conveying dry bulk materials with positive displacement blowers,” explained Adam Crampton, Regional Sales Manager at MD-Kinney. “Dense phase pneumatic conveying, on the other hand, involves conveying products at higher pressures, usually 14 to 15 psig and greater, at a low velocity. The product is not suspended in the conveying line. Cereals, pet food, and other dry, fragile products susceptible to degradation are commonly transported via dense phase conveying.”

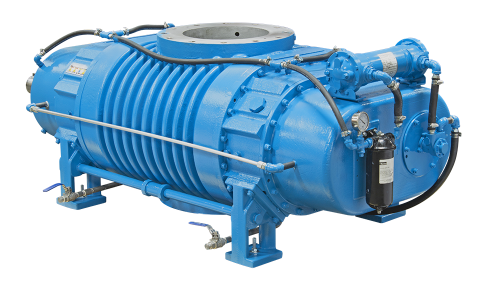

The most common way to move dry bulk materials is with positive displacement blowers, such as the PD plus pictured above.

Selecting Blowers for Pneumatic Conveying

MD-Kinney engineers take a number of variables into consideration when selecting the ideal blower for a pneumatic conveying application. First, the flow rate and pressure required to move the material needs to be understood. Secondly, the temperature of the air or gas at both the inlet and discharge of the blower are significant factors, as they will have a direct impact on the material being conveyed.

“With pneumatic conveying, you are moving a solid material from one location to another by using air as a transportation media,” said Tim Wilson, Project Engineer, MD-Kinney. “Designating a blower starts with understanding the material. Does the product behave well within that media at a given temperature? If the blower is performing at a high pressure, then we may have to look at sizing an after-cooler downstream of the blower to cool the gas so we still have the pressure we need, but at an appropriate temperature for the material.”

Other material properties also need to be considered, such as bulk density, material hardness, stickiness, and abrasiveness. Additionally, since you are moving the material from one point to another, the transportation path must be evaluated. Variables might include the number of vertical runs, horizontal runs, and elbows along the conveyance line. Those specifications, in addition to pipe diameters, will help determine the pressure, flow, and blower flange or core size.

The new MD-20 Blower Package is ideally suited for pneumatically conveying products where operating noise isn’t a factor to production.

Blower operating speed is also evaluated to ensure the blower operates within a healthy area of its performance curve. “Blowers are designed to operate at full speed, or 100 percent of the design, and they work well there,” Wilson said. “In a pneumatic conveying system, the challenge can be sizing the blower. If you size a blower for 100 percent of its rated speed, get it installed, and then need to move more product, then you are limited. Designing the system to operate at about 70 to 80 percent of its design capacity is a good practice—that way the design has some room for adjustments.”

Finally, the installation location of the blower needs to be considered on an application-specific basis, as operating noise can be an issue. “Blowers are, by in large, fairly loud,” Wilson commented. “If it’s outside and no one is around, we won’t often see a noise requirement on an installation. However, it’s common in the food and beverage industry to install blower packages indoors. People are often in the area, so sound enclosures are frequently used.”

MD-Kinney blower offerings include the CP Series, the Equalizer, the PD plus, and the QX, along with blower packages for installations with sound requirements. In addition, dry bulk and mobile truck blowers are often used in the food manufacturing industry to move materials like flour. Transported on a trailer, mobile blowers from MD-Kinney include the T650, T850 and T1050. They are used to convey product from a trailer to a silo or rail car, and can be used for vacuum conveying to load material into the truck’s trailer.

The M-D Pneumatics T855 blower is specifically designed for transport applications where products need to be pneumatically conveyed.

Opportunities for Retrofitting Vacuum Systems on Manufacturing Equipment

Change can be intimidating, especially if it concerns the reliability of a major piece of manufacturing equipment. The vacuum systems of food processing machines, for instance, could be ripe with opportunity for improving process speed and enhancing reliability, but end users may not want to tweak the system. “Because a rotary vane pump comes with a certain kind of machine, people may be afraid to make a change,” Ristow explained. “The customer may not know it, but there are a lot of other options out there.”

Ristow discussed vacuum pumps in meat packaging machines as an example. Traditionally outfitted with oil-lubricated rotary vane pumps, meat packaging machines can benefit from piston pumps. Normally requiring at least 500 microns of vacuum, or 0.5 Torr, meat packaging applications demand fast cycle times. The most prevalent issue, however, is handling water vapor.

“With a piston pump, you have a much larger oil sump than you would with a rotary vane pump for the equivalent vacuum system, and the gas ballast will actually allow you to handle more water vapor,” Ristow explained. “As time goes by and the oil begins to degrade, the piston pump will last longer while holding ultimate vacuum, because it will pull a little deeper than a standard rotary vane pump. And it’s a lot more rugged. In meat packaging applications, piston pumps are not a bad way to go, but people frown on it because they are not familiar with the technology. You really need to look at the process, evaluate what’s best for the customer, and then decide what technology is available.”

Retrofitting Vacuum Systems in Pickle Packaging

Keep this in mind: Replacing the vacuum pump on a machine will not automatically solve reliability problems, or improve cycle times. Ristow stressed the importance of evaluating the entire system, and discussed a sliced deli pickle manufacturer located in California as an example. The facility wanted to achieve faster cycle times on a vacuum sealing machine (similar to a roll stock machine). To do so, they brought in a third party, who recommended installing larger vacuum pumps. Much to the plant’s dismay, there was no progress in production. Frustrated with lack of improvement, plant personnel contacted MD-Kinney to fix the issues.

The packaging process was designed around cycle time using thin film, and needed 28”Hg to properly seal the pickles. With flow requirements of about 300 cfm, the third party recommended replacing the original 50-cfm vacuum pumps with machines capable of providing between 150 and 200 cfm of airflow. What they failed to account for, however, was the size of the inlet piping and orifices.

“We found out it was their plumbing that was the concern,” Ristow said. “They had 1.5-inch piping on the inlet. They thought they would get more capacity, but there was too much friction on the inlet orifice. In addition, they were using right angles instead of using 45° angles, which was affecting the conductance. That is one of the things you need to look for as an end user when you make those changes. You have to make sure your connections are adjusted too.”

In addition to airflow issues, the facility also experienced problems with maintaining the larger, oil-lubricated vacuum pumps. “In pickle packaging, there is a concentration of brine, salt, and other acids that can be corrosive and affect the pH levels,” explained Ristow. “There is a lot of moisture involved in it too, so as you pull vacuum, the water and other ingredients from the pickling process have a tendency to turn into a vapor and work their way into the pump. In this case, it was attacking the oil and the materials of construction on the vacuum pumps, causing maintenance issues.”

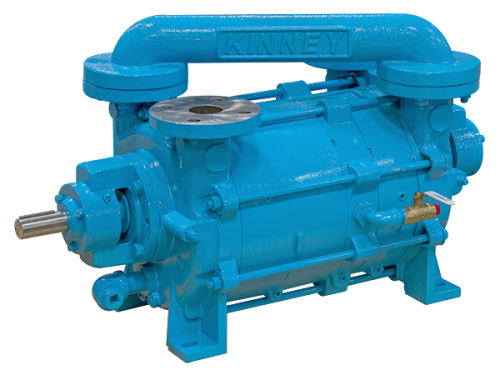

Instead of oil-lubricated pumps or dry vacuum technology, MD-Kinney installed liquid ring vacuum pumps that met the vacuum levels required. Constructed with stainless steel componentry, the liquid ring pumps could more effectively deal with the amount of brine and water vapor involved in the process.

“Everybody is moving towards dry pump technology, but I don’t know if I’d necessarily put a dry pump into a pickle packaging application,” Ristow said. “Because of the brine and acids produced from the pickling process, the corrosiveness could eventually attack the screws—unless you put some kind of coating on it. In this case, I think a liquid ring was best because it has wider, or larger tolerances, so it’s more forgiving when it comes to taking in solids or processing a corrosive gas. And you can use different types of sealant other than just water. For this process, water was the best option, but it depends on the vapor pressure of the sealant and how it best fits within the application.”

MD-Kinney determined that a Kinney liquid ring pump could more effectively handle the large amount of brine and water vapor involved in the pickle packaging application.

Centralized Vacuum System for Whey Manufacturing

Apart from retrofitting packaging machines, engineers at MD-Kinney design centralized vacuum systems to improve overall performance at food plants. One example involved a dairy manufacturing facility, which primarily produced whey. At this plant, the dehydration process required vacuum levels of 29.9”Hg in order to effectively dry dairy product moving through the plant. The facility originally had individual vacuum pumps installed in each of its stainless steel evaporation vats. Plant engineers contacted MD-Kinney to centralize the system, and to install it 100 feet away from the end uses on a mezzanine.

Where a traditional vacuum system might run piping to every application separately—with each individual run creating a straight line from the vacuum pump to the process—a centralized vacuum system uses a circular piping header to feed every process. Drops are then made to each application. When installing a central vacuum system, you need to evaluate the plumbing, and understand how pressure drop will impact the system. According to Ristow, it is especially important to understand minimum pipe diameter. “Minimum, I think, is more important than your maximum,” he said. “Obviously cost is a factor: You don’t want to go to 12-inch piping as a minimum, but you don’t want to go too small. You want to use the piping as a receiver, which can be cost effective.”

For the whey manufacturing facility, MD-Kinney installed the centralized vacuum system per the customer’s requests. They provided a rotary vane pump to supply the system, and the circular header now acts as a larger plenum for more efficient operation. The new system has several other benefits as well, aside from the reduction in horsepower. “Going from multiple vacuum pumps at each vat to two larger ones eliminates a couple of issues,” Ristow explained. “For this system, you need less oil changes. It still might take the same amount of oil, or just a little bit less, but it’s more efficient when it comes to maintenance. Additionally, with multiple pumps, you need to keep more filters on hand, and keep more stock.”

Replacing Vacuum Pumps with Centralized Blower Systems

MD-Kinney’s engineers have also identified energy-saving opportunities when changing from individual vacuum pumps to centralized blower systems. One example involved a tea manufacturing plant, where tea was made and then packaged. Their packaging machines each had a 1-hp vacuum pump installed on the unit, as specified by the OEM. Ristow was able to replace those 10 units with a duplex central blower system, thereby reducing the amount of energy required to run the system, and eliminating noise factors.

“For this facility, they didn’t need much vacuum: The pumps could pull 25”Hg, but the requirement was less than 15”Hg, which a blower package could handle,” Ristow explained. “Again, the manufacturer said what you needed, but in reality, it was less. The central blower system also took noise and heat out of the equation, so there are a lot of advantages of a central station other than just energy efficiency.”

By the end of the project, MD-Kinney replaced the 10 vacuum pumps with a 2 x 3-hp blower package, reducing overall energy use. The central blower package also provided extra capacity for the manufacturing plant to grow. “Another misconception in the food industry is that issues are related just to the vacuum level, when they could be related to flow ” Ristow said. “This facility wanted to grow, which was one advantage of the blower system—you could actually increase the capacity for additional flow demand. All you had to do was change the pulley size to speed that blower up. With a blower package, you have more versatility with flow, and you are not limited just to the standard rpm of an individual vacuum pump. While it could potentially be slowed by a VFD, many times vacuum pumps can't be run faster than their original motor’s design criteria.”

Examining Examining Vacuum and Blower Systems in Food Plants

Vacuum and blower systems within a food plant are vital pieces of the production puzzle. Consequently, they should be scrutinized to optimize production throughput, energy efficiency, and reliability. MD-Kinney understands the application-specific nature of these systems, and works to engineer the proper solution every time—whether it is a blower system for pneumatic conveying, a centralized vacuum system for producing whey, or retrofitting individual vacuum pumps on large packaging machines.

For more information, visit https://www.md-kinney.com/en-us.

To read more about Blower and Vacuum System Assessments, please visit www.blowervacuumbestpractices.com/system-assessments.